Deserted Communities of the Sahel : A Humanitarian Crisis of a Continent

By Katya Sharma

On March 2nd, 2018, several gunmen opened fire on the French embassy in Burkina Faso’s capital. Over thirty people died in the terrorist attack, and over eighty were injured (Khan, 2018). This attack was the third assault in the capital of Burkina Faso, Ouagadougou, in a little over two years (“Burkina Faso's Capital Hit by Coordinated 'Terror' Attacks”). One day before the attack in March in Burkina Faso, Boko Haram carried out an attack on a military base in Nigeria. In 2017, 67 fatalities occurred, and in 2016, at least 213 fatalities occurred in Nigeria due to terrorist attacks (Khan, 2018).

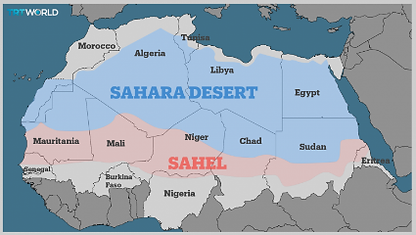

The Sahel region stretches across Africa from the Atlantic Ocean to the Red

Sea, and acts as the transitional region between the Saharan desert and the

Savanna to the South (Magin, 2003). It borders countries such as Mali, Niger,

Nigeria, Burkina Faso, Senegal, and more. While 2017 marked a drop in fatalities

associated with terrorism in the Sahel (10,376 compared to a peak of 18,728

in 2015), activity by Islamic militancy has increased, in particular the number of

violent events in 2017 (2,769 events from 2,317 in 2016) (“More Activity but Fewer

Fatalities Linked to Africa's Militant Islamist Groups in 2017”).

To understand the socioeconomic context of this dramatic increase, Nigeria

acts as an epitome. Nigeria has the largest population and highest GDP in the

continent of Africa, however the wealth and progress is concentrated to the South. The North, the region that is a part of the Sahel, hosts a poverty strife, marginalized, and isolated muslim population (over 40%). Over half of Nigeria’s population live on less than $1.90 per day and poverty is considerably more rampant in the North, due to, “... a small number of elites that maintained a tight hold on oil revenues, and corrupt government ministers [in Laos] (Felter, 2018).”

Boko Haram was founded in the north-eastern state of Borno in Nigeria, initially established as a school and a religious complex. As the founder denounced the government by connecting corruption to the Westernization of the state, he attracted a vast amount of unemployed youth, in attempts to, “...establish a fundamentalist Islamic state with sharia criminal courts (Felter, 2018).” In 2008, security forces searched the Boko Haram premises amid rumours that the group had begun to arm itself, discovering bomb-making equipment and a multitude of weapons. Eventually, the founder of the group was arrested and died in custody under suspicious circumstances spurring a wave of retaliation from the fundamentalist group (“Who are Nigeria's Boko Haram islamist group?”).

The Nigerian government attempted to crackdown, however the group grew exponentially

in numbers evolving into an entity more deadly than ISIS in 2015 and 2016 (Martin, 2017).

In 2014 the group received international attention after the abduction of 300 school girls,

and at that instant it controlled a large part of north-eastern Nigeria. In response, five

African states’ militaries, backed by the French, UK, and US military fought Boko Haram

and liberated major cities, pushing them into the Lake Chad region, which borders Niger,

Nigeria, and Chad (Ellis, 2018).

While they have been pushed back to the deeply forested region, Boko Haram has merely

shifted its focus to the Lake Chad region. The FAO director-general reported that since

1963, “... Lake Chad has lost some 90 percent of its water mass with devastating

consequences on the food security and livelihoods of people depending on fishing and

irrigation-based agricultural activities. And while Lake Chad has been shrinking, the

population has been growing, including millions of displaced people from the worst

conflict areas (Mayer, 2018).” This dramatic decrease in agricultural capability has pushed

the region into a food crisis. According to the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP),

“the ‘ecological’ catastrophe that is Lake Chad has deceased from approximately 25000 km²

in 1963 to less than 2500 km2, threatening the resources and livelihoods of the 50 million

people (expected to double by 2030) that live there (Kingsley, 2016).”

This environmental disaster has exacerbated the poverty of, “one of the poorest regions in the world (Ellis, 2018).” Following the military operation Boko Haram began operating in this region, raiding villages and displacing up to 3 million people by 2017. The group eventually split in two due to internal dispute over the brutality of Boko Haram, creating a seperate group called the Islamic State of Western Africa (ISWA). They are officially affiliated with the Islamic State in the Levant, and offer the villages in the area protection against Boko Haram and even water supplies in a region crippled by a food crisis: one in three families in the Lake Chad Basin is facing extreme food insecurity, and a total of 17 million people in the region are affected by this hunger crisis (Duckworth, 2017), in exchange for taxes and recruits. Without the presence of any real government ISWA has regained territory in North-East Nigeria.

The complicated situation of the Lake Chad Basin highlights the dire consequences of the lack of government in areas. Dimouya Souapebe, a government official in Nigeria, said, “...it was easy for Boko Haram to come in from Nigeria and poison people’s minds,” by promising access to basic services and Islamic education. “The islanders never had a school. They’ve never had sanitation. They drink the same lake water they defecate in. Out in the islands, there is nothing (Taub, 2018).”

This is not a crisis limited to the countries bordering the Lake Chad Basin, in fact the entirety of the Sahel suffers from the same complications. This entire strip of Africa acts as fertile grounds for Islamist militant groups, as was seen seven years ago, when an Islamic militia occupied the north of Mali and declared it an Islamic Caliphate for ten months, another heavily neglected region. Again, French military intervened and pushed them into the desert, where the group affiliated with ISIS and Al Qaeda, and returned to perpetrate terrorist attacks against the French embassy and American troops. A similar phenomenon has occurred in Somalia, with the Al-Shabaab terrorist group, and furthermore ISIS in Libya perpetrated ten attacks this year itself.

This phenomenon has made this region one of the most dangerous in the world, causing France and the USA to step up military presence within the Sahel. However, the rise in Islamist terrorism cannot be combated with drone strikes and intervention, because as long as there is rampant poverty, no food security or health services, and no education, and no government presence, people will turn to these groups in the hopes of a better life.

Bibliography :

“- Burkina Faso's Capital Hit by Co-Ordinated 'Terror' Attacks.” The Irish Times, The Irish Times, 2 Mar. 2018, www.irishtimes.com/news/world/africa/burkina-faso-s-capital-hit-by-co-ordinated-terror-attacks-1.3413044.

- Duckworth, Saru. “Speaking About Lake Chad Basin Hunger and Poverty.” The Borgen Project, The Borgen Project, 18 July 2017, www.borgenmagazine.com/lake-chad-basin-hunger-and-poverty/.

- Ellis, Sam. How Islamist Militant Groups Are Gaining Strength in Africa. Vox Atlas, Vox, 20 June 2018, www.youtube.com/watch?v=U2gvha4CipY&t=169s.

- Felter, Claire. “Nigeria's Battle With Boko Haram.” Council on Foreign Relations, Council on Foreign Relations, 8 Aug. 2018, www.cfr.org/backgrounder/nigerias-battle-boko-haram.

- Khan, Shehab. “At Least 35 People Die after a Series of Terrorist Attacks in Burkina Faso.” The Independent, Independent Digital News and Media, 2 Mar. 2018, www.independent.co.uk/news/world/africa/burkina-faso-terrorist-attacks-casulties-jihadi-islamic-extremism-a8237346.html.

- Kingsley, Patrick. “The Small African Region with More Refugees than All of Europe.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 26 Nov. 2016, www.theguardian.com/world/2016/nov/26/boko-haram-nigeria-famine-hunger-displacement-refugees-climate-change-lake-chad.

- Magin, Chris. “Sahelian Acacia Savanna.” WWF, World Wildlife Fund, 2003, www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/at0713.

- Martin, Jenna. “A Closer Look at 5 of the Most Dangerous Terrorist Groups on the Planet.” SBS, Vice News, 12 June 2017, www.sbs.com.au/guide/article/2017/06/13/closer-look-5-most-dangerous-terrorist-groups-planet.

- Mayer, Peter. “Lake Chad Basin: a Crisis Rooted in Hunger, Poverty and Lack of Rural Development - Nigeria.” ReliefWeb, Food and Agriculture Organization, 11 Apr. 2017, www.reliefweb.int/report/nigeria/lake-chad-basin-crisis-rooted-hunger-poverty-and-lack-rural-development.

“- More Activity but Fewer Fatalities Linked to Africa's Militant Islamist Groups in 2017.” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 26 Jan. 2018, www.africacenter.org/spotlight/activity-fewer-fatalities-linked-african-militant-islamist-groups-2017/.

- Taub, Ben. “Lake Chad: The World's Most Complex Humanitarian Disaster.” The New Yorker, The New Yorker, 23 June 2018, www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/12/04/lake-chad-the-worlds-most-complex-humanitarian-disaster.

“- Who Are Nigeria's Boko Haram Islamist Group?” BBC News, BBC, 24 Nov. 2016, www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-13809501.

Images :

- Carsten, Paul. “Nigerian Military Struggles against Islamic State in West Africa:...” Reuters, Thomson Reuters, 19 Sept. 2018, www.reuters.com/article/us-nigeria-security-military/nigerian-military-struggles-against-islamic-state-in-west-africa-sources-idUSKCN1LZ1IF.

- Massalaki, Madjiasra Nako and Abdoulaye. “Chad, Niger Launch Joint Offensive against Boko Haram in Nigeria.” Yahoo! News, Yahoo!, 9 Mar. 2015, www.yahoo.com/news/chad-niger-launch-joint-offensive-against-boko-haram-064402641.html