Are there more hurricanes today? A quick survey featuring 2 hit songs tells us yes

By Anonymous

This year, Hurricane Dorian, a category 5 major hurricane, swept through the Bahamas. More than 60 people were killed, 70,000 were left homeless, and daily life was completely disrupted with massive flooding and loss of even the most basic forms of infrastructure. While it’s easy for us to think of hurricanes as singular events, for people of hurricane-prone regions, it is a recurring reality that brings fear and panic, loss of life, and widespread destruction of crops and property. This article briefly looks at two tropical storm seasons across the world, highlighting how hurricanes are annual events that are only becoming deadlier; and how we need to push now — more than ever before — for greater corporate responsibility, sustainable development, and more infrastructural projects in hurricane-prone regions.

1988 Atlantic Hurricane Season

“Aruba, Jamaica, oh I want to take you to

Bermuda, Bahama, come on pretty mama

Key Largo, Montego, baby why don't we go

oh I want to take you down to

Kokomo, we'll get there fast and then we'll take it slow

That's where we want to go, way down in Kokomo”

… sing the Beach Boys in their hit song Kokomo, about two lovers vacationing on an island off the Florida Keys. They paint a pretty picture of the islands of the Caribbean; but if you were the recipient of Mike Love’s serenade when the Beach Boys first released this hit song in 1988, would it have been a great idea to “get away from it all” in Aruba or Jamaica?

1988 saw 5 hurricanes in total, slightly lower than the 11-year mean of 5.5 hurricanes (see table 1 below); so one might imagine that taking the weekend off in Jamaica’s Montego Bay would have been quite a safe bet.

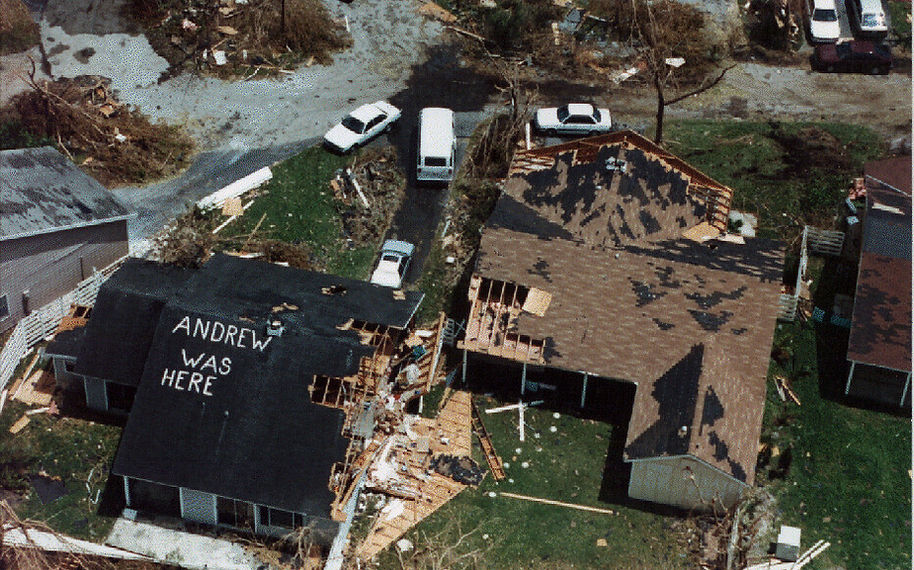

But chances are, had you been in Jamaica in September 1988, you would probably have spent more time indoors putting black tape over your hotel windows than basking outside in the sun. Hurricane Gilbert, a category 3 hurricane, made landfall in Jamaica on September 12, passing directly over the island. The ensuing rain and winds brought flash flooding, destroyed more than 100,000 houses (taking away the roofs of more than 80% of all houses on the island), and killed more than 30 people. Gilbert intensified as it left Jamaica and crossed the Caribbean Sea, reaching category 5 as it hit the Yucatan Peninsula, and struck a new record for the strongest Atlantic Hurricane ever seen at that time — a record that would not be defeated until 2005’s Hurricane Wilma.

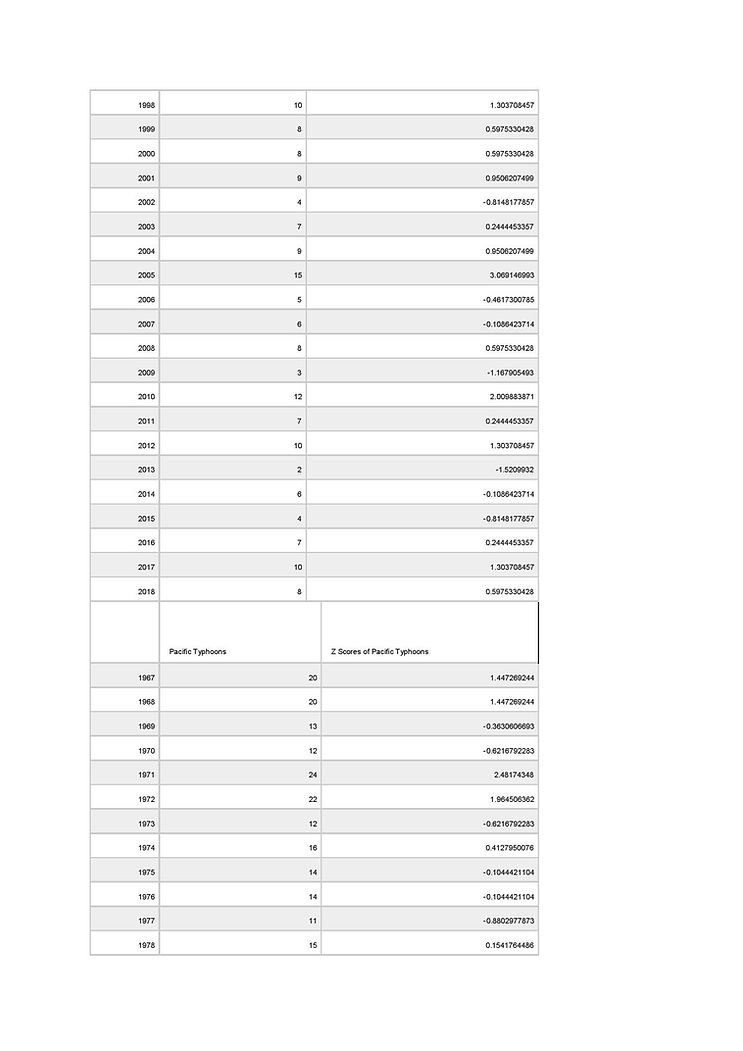

Have things changed for the better? Taking a dataset of the number of Atlantic hurricanes during each yearly season from 1967-2018, and standardising the data to find z-scores, reveals that the more recent period spanning 2000-2010 instead saw higher frequencies of hurricanes from the mean compared to the period 1980-1990. (Refer to Table A1 in the appendix)

2017 Pacific Typhoon Season

“The flowers sway back and forth in the wind

I think about you till midnight

I hope the moonlight brings you back to my side

I believe my love will allow me to find you”

In another part of the world, and almost 30 years later, Taiwanese pop singer Crowd Lu strums his guitar as he performs a ballad, 魚仔(Fishes), in Taiwanese Hokkien about rekindling a lost love. While it did not literally rain fishes in 2017— as it did in India after 2018’s Cyclone Phethai (see this video) — the 2017 Pacific typhoon season saw 11 typhoons, a number that despite seeming high, renders 2017 below-average in typhoon frequency and strength. In fact, 2017 failed to see the formation of a category 5 typhoon — the formation of which had till then occurred every year since 1977.

Despite the numbers pointing at 2017 being a year featuring weaker typhoon activity, typhoons still continued to devastate local populations — a reflection of the daily realities of people living in locales vulnerable to tropical storms, and the effect climate change has had on the intensity and frequency of these storms. Taiwan was struck by Typhoon Nesat, a category 2 typhoon, on July 29 2017. Despite the preparations the country makes every year to defend against typhoons, the country nevertheless saw 500,000 households left without electricity, schools left significantly damaged, and 10,000 people forced to evacuate. This disruption to daily life was further intensified by Tropical Storm Haitang, which followed immediately in the typhoon’s wake. In Japan, 4 months after Typhoon Nesat, 381,000 people were evacuated when Super Typhoon Lan made landfall over Omaezaki in Shizuoka. The storm killed 17 and caused agricultural losses of more than USD 540 million.

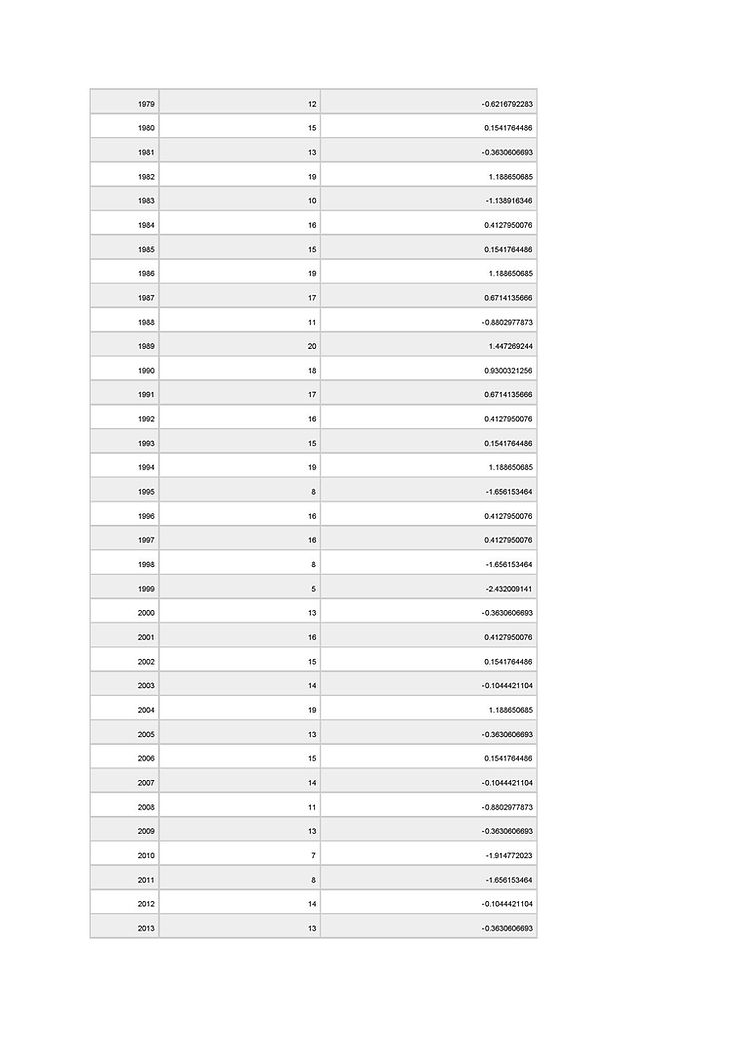

When taking the dataset of the number of Pacific Typhoons during each yearly season from 1967-2018, and standardising the data to find z-scores, what is interesting is that most of the years in the last decade record a lower number of typhoons than the dataset mean. In fact, the z-score for the last 20 years averages at 0.4 standard deviations below the mean. (Refer to Table A2 in the appendix)

While this does mean that we are seeing fewer pacific typhoons of late, it does not mean that these tropical storms aren’t causing fewer humanitarian disasters. Typhoons remain just as, if not more, costly and deadly. Kang and Elsner from the American Meteorological Society find in 2015 that occurrences of tropical cyclones are falling slightly, but those that do form are likely to reach extreme intensities. Furthermore, they found that climate change most significantly influences the upper portion of extreme typhoon intensities. Similar results were found by Jagger and Kossin researching at Florida State University, and Holland and Bruyere with the National Centre for Atmospheric Research.

It’s difficult to make generalisations about the sorts of relationships between climate change and the frequency and intensity of tropical storms around the world. Not only because there are a multitude of different factors beyond climate change, but also due to the differences between the Atlantic, East Pacific, and West Pacific weather systems. Some trends are clear however — whether a new higher baseline in the frequency of Atlantic hurricanes (as popularly reported by Vox), or a new normal in the Western Pacific with above-normal-to-extreme accumulated cyclone energy. Vulnerable communities and governments in these regions need to adjust to this new reality, and the fortunate ones amongst us who find ourselves outside of these regions shouldn’t just stand idly by.